One of the finest results of the 400th anniversary of the death of a certain man from Stratford has been the increased availability of digitised original texts connected to Shakespeare. The Folger’s Shakespeare Documented project is a treasure trove, though in many cases one should take the write-ups with a pinch of salt. It is quite a stretch, for example, to claim that a report from 1633-43 that the name “Shakespear” was carved into the panels of tavern alongside those of other famous people of the day is ‘a unique record of Shakespeare, at the peak of his career, gathering with friends and colleagues at the Tabard inn in Southwark’. Unless someone can furnish us with evidence the people in question did their own carving, it sounds more like the landlord paying homage to some local celebrities and trying to increase the cachet of his hostelry by association. But I digress.

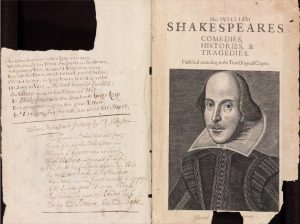

As a scholar whose specialist subject is the authorship question, my eye tends to fall on those offerings that orthodox scholars miss: items that so strongly resist fitting in with the traditional story that they will be passed by as nonsensical or unimportant. This week, a fresh oddity was brought to my attention, and if you’re at all interested in the idea that Christopher Marlowe might have authored the Shakespeare canon (the premise of my first novel), I think you’ll like it too.(1) You will find it opposite the title page of the newly digitised Bodleian First Folio. Follow that link, flip forward two pages, and see it for yourself.

A new First Folio find

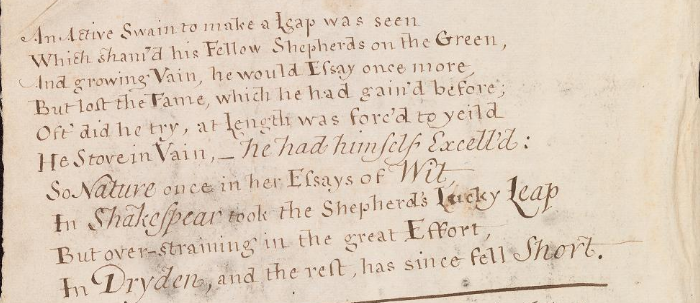

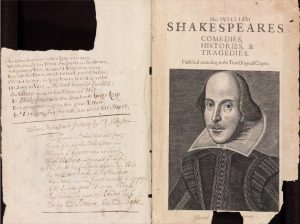

The usual page containing Ben Jonson’s 10-line poem facing the Droeshout engraving, and telling the reader seeking the author to ‘looke/Not on his Picture, but his Booke’, has been removed. On the blank page that remains, someone has written a replacement 10-line poem that reads as follows.

An Active Swain to make a Leap was seen

which sham’d his Fellow Shepherds on the Green,

And growing Vain, he would Essay once more,

But left the Fame, which he had gained before;

Oft did he try, at length was forc’d to yeild

He st[r]ove in Vain, – he had himself Excell’d:

So Nature once in her Essays of Wit,

In Shakespear took the Shepherd’s Lucky Leap

But over-straining in the great Effort,

in Dryden, and the rest, has since fell Short.

[I have tried to reproduce it as the author intended, including those words and phrases in italics; I have left the spelling of ‘yeild’ alone, though it is wrong to modern eyes. I think it fair to assume from the context that ‘strove’ rather than ‘stove’ was intended.]

I imagine the title of this poem might have been instructive, but it has been removed. Presumably it was offensive to someone; perhaps the same person who wrote ‘Honest [Will? Shake]peare’under the portrait, or the person who copied back in, by hand, the poem that should have been on this facing page. We are fortunate the poem itself survived.

The Dryden reference helps date the poem: John Dryden was made Poet Laureate in 1668. The Bodleian First Folio is a rarity for not having been re-bound since it was first donated to the library in 1623. The library ‘appears to have sold it at some point in the late 1660s, perhaps having replaced it with the new, improved, edition, the Third Folio, with its additional plays, which was published in 1663/4.’ So it seems likely that ‘An Active Swain’ was written into the Bodleian First Folio not long after this: during Dryden’s dominance: 1668-1700. The anonymous author need only be one or two generations removed from Shakespeare’s generation: in a position to have had information directly from their father or grandfather.

Like many of the anomalous writings connected to the Shakespeare canon, this poem is written in such a way that its meaning is deliberately veiled. To someone convinced of the traditional narrative, it will look like nonsense (essential for preservation: not worth destroying, though the title clearly was). But if you look at the words through a particular lens, you may get a little more clarity. I am choosing to look at it through a Marlowe-shaped lens because there seem to be some strong points of connection with that theory.

Shakespeare and another poet

This is a poem about the author known as Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s name is mentioned in the 8th line, and the poem has been deliberately placed opposite the Droeshout engraving, replacing Ben Jonson’s instructions about how to approach the First Folio. It speaks of a separate poet, an ‘active swain’, later referred to as a shepherd. Swain or shepherd was a common pastoral term for poet. Christopher Marlowe was referred to as a shepherd in As You Like It when Rosalind quoted a line from Marlowe’s Hero and Leander:

Dead shepherd, now I find thy saw of might:

Whoever loved, who loved not at first sight?

But the term does not identify an individual. So the poem begins by saying there was ‘an active poet’. The poet cannot be equated with Shakespeare because line 8 makes it clear they are separate: that Nature, ‘in Shakespear took the Shepherd’s Lucky Leap.’ What is this ‘leap’? We’ll come back to that, through a Marlowe-shaped lens.

This poet made a ‘leap’.

Lines 1 and 2 tell us:

An Active Swain to make a Leap was seen

which sham’d his Fellow Shepherds on the Green

The poet made a leap which shamed his fellow poets (who are on ‘the green’ because this is what pastoral poets do, of course, sit about on the grass). What kind of leap could that be? With Marlowe, take your pick.

- An artistic leap. Only in his twenties, he took blank verse drama to a level it had never been before. The two-part Tamburlaine was a huge hit, as was Doctor Faustus. Jonson refers to ‘Marlowe’s mighty line’ in the preface of the First Folio. Most orthodox scholars accept that Marlowe was a genius who paved the way for Shakespeare. Swinburne said

‘He first, and he alone, guided Shakespeare into the right way of work… Before him there was neither genuine blank verse, nor genuine tragedy in our language. After his arrival, the way was prepared; the paths were made straight, for Shakespeare.’

- A social leap. A cobbler’s son, he won scholarships to grammar school and university, gaining an MA (then the highest qualification) and by so doing, officially gaining the social status of Gentleman. The most powerful men in the land (the Privy Council) wrote to Cambridge University in his support, saying he had ‘done her Majesty good service … in matters touching the benefit of his country’. He became ‘very well known’ to high ranking noblemen Lord Strange (5th Earl of Derby) and Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland. He dedicated a work to Mary Sidney, the Countess of Pembroke; new research (in press) consolidates his connection to her social circle. He was also part of Sir Walter Raleigh’s circle of free-thinkers and Raleigh wrote a response to Marlowe’s The Passionate Shepherd to his Love. (And there’s that Marlowe/shepherd connection again).

Both artistically and socially, Marlowe outstripped his peers, putting them to ‘shame’ as the poem describes. According to the poem, this ‘leap’ led to the poet ‘growing Vain’. Gabriel Harvey’s ‘Gorgon’ poem, written in 1593 and mentioning ‘thy Tamburlaine’, contains a contemporary accusation of Marlowe’s vanity:

He that nor feared God, nor dreaded Div’ll,

Nor ought admired, but his wondrous selfe:

Like Junos gawdy Bird*, that prowdly stares

On glittring fan of his triumphant taile

* peacock

This poet ‘left the fame’.

Lines 3 and 4 tell us:

And growing Vain, he would Essay once more,

But left the Fame, which he had gained before;

These are very interesting lines, don’t you think? Can you tell me of a famous poet (for the poem is explicit: he had ‘Fame’) – who ‘left the Fame, which he had gained before?’ Generally when poets become famous, they stay famous during their lifetimes. These lines are a fine fit for the Marlowe theory, which includes the reluctant abandonment of fame. The theory goes that he was forced to fake his death (which occurred while he was effectively ‘on bail’, having been arrested ten days earlier) to escape being executed for atheism, then considered treason. A faked death of this kind would not be technically difficult, given Marlowe’s high-placed connections and his work for the Elizabethan secret service. Roy Kendall, biography of Marlowe’s nemesis, Richard Baines, has noted ‘deaths in the murky world of espionage can often be “blinds” for disapearances, and vice versa’. But a faked death would be emotionally very difficult indeed for a successful and vain young man, who ‘would Essay once more’ (‘would’ = ‘would like to’; best fit for the verb form of ‘Essay’ from the OED: try/accomplish).(2)

There was a struggle and the poet lost.

Lines 5 and 6 tell us:

Oft did he try, at length was forc’d to yeild

He st[r]ove in Vain, – he had himself Excell’d:

The poem doesn’t tell us what he tried ‘oft’. One wonders if there is a link here with the previous verb, ‘essay’, which means both try and accomplish, and is linked (through its noun form) to writing. All we know is that no matter how much he tried, he tried in vain, and was ‘forced to yield’. To whom or what? And what does this have to do with Shakespeare’s First Folio, in which the poem is so deliberately written? If we read the reference as Marlowe’s struggle to be ‘resurrected’ or at least have his works attributed to his own name, the words directly opposite the poem: ‘Mr William SHAKESPEARES Comedies Histories & Tragedies‘ are the record of his defeat. And why? Because ‘he had himself Excell’d‘.

The poet excelled himself.

The first argument against Marlowe authoring the Shakespeare canon is “wasn’t he dead?”; the second is “Marlowe’s works aren’t as good as Shakespeare’s”. But this is to compare the works of a (brilliant but inexperienced) twenty-something (everything in the Marlowe canon was written by the time he was 29) with a writer allowed to reach his prime. Doctor Faustus and Edward II are accomplished plays but Lear, Othello, and Hamlet came twenty years later; twenty years extra reading, life experience, writing practice, and ‘striving’. If you look at the combined Marlowe-Shakespeare canon in the order in which it was written, the transition is actually pretty smooth. The early Shakespeare plays (e.g. the Henry VI trilogy, The Taming of the Shrew) were often attributed all or in part to Marlowe until the 1920s; Titus Andronicus (c.1594) is incredibly Marlovian. Late Marlowe and early Shakespeare segue one into the other without a hiccup.

‘He had himself Excell’d’ is clearly important: it is the only phrase in the poem that the author has emphasised by writing it in italics. The solitary dash clearly indicates that ‘excelling himself’ is the cause of the poet’s failure (to achieve what he was trying to achieve). Under what circumstances could a poet’s excellence lead to their failure? If Marlowe was the central author of the Shakespeare canon this line makes perfect sense. Having excelled himself, Marlowe could not be attributed with the surpassing genius of the Shakespeare canon.

The poet’s ‘lucky leap’ is ‘in Shakespear’.

Lines 7 and 8 tell us:

So Nature once in her Essays of Wit,

In Shakespear took the Shepherd’s Lucky Leap

We start with ‘So’: this is a solution to the problem that the poet couldn’t succeed at his striving (to be credited with his own works?) because ‘he had himself excell’d‘. The noun form of ‘essays’ in the 17th century most commonly meant ‘trials’ – so a modern translation of the phrase in line 7 could be ‘trials of wit’.(3) But since the modern meaning of the noun ‘essay’ was in use at this time, there may also be an intended hint of ‘witty writing’. It is the poet who has been trying, striving, and essaying, and perhaps here it is the poet’s ‘Nature’ that is implicated. ‘Nature‘ is being credited for something whose mechanism we do not understand. You might think of it as something like the poetic muse, that mysterious creative force. But how to explain the next line?

‘Shakespear’ contains the poet’s ‘lucky leap’ – that leap, we remember, that set him apart from his ‘fellow [poets]’, put them to shame, and made him vain. But how might we account for that interesting adjective ‘lucky’? So many other two-syllable adjectives might have been chosen to make the metre, and one might fairly ask how the poet’s ‘leap’ – the excellence that apparently led to failure, despite all his striving – could be described as ‘lucky’. Again, Marlowe theory to the rescue. It would be fair to say that someone slated for a grisly execution (hanging, drawing and quartering being standard for treason) and whose secret service colleagues helped them escape into exile might said to be ‘lucky’ to be alive, even though they had lost control of their writings. Under the Marlowe theory, Marlowe’s ‘lucky leap’ – the blessed escape which allowed him to continue writing and developing as a writer, and all the wisdom that such an experience would bring – ends up ‘in Shakespear’ – in this book of plays that appear under the Shakespeare name.

The poem explains why ‘Shakespeare’ is unsurpassed.

Lines 9 and 10 tell us:

But over-straining in the great Effort,

in Dryden, and the rest, has since fell Short.

It is Nature, we remember, who has over-strained in this effort: the effort presumably being the same one referred to with the words ‘try’ and ‘st[r]ove’. And the final lines explain that no writer since has come close to the brilliance we find in the canon called Shakespeare. The poet’s striving to overcome his circumstances (the circumstances that involved leaving his fame behind) led to him excelling himself with a genius (contained ‘In [the works of] Shakespear[e]’) that has never been surpassed or even equalled. Not at the time this poem was written, and not since.

‘Nature’ is shorthand. The excellence of Shakespeare, through the Marlowe-shaped lens, is due to the shaping force of an extraordinary experience on an already extraordinary creative mind. The genius found ‘In Shakespear’ is not equalled because the author’s experience of suffering has not been equalled. It was suffering that brought wisdom, as suffering often does, giving this singular author a broad perspective, and profound human understanding.

Points to ponder

Consider Shakespeare’s obsession with name, with exile, with mistaken identity, with resurrection.

Consider some of the otherwise inexplicable lines of the Sonnets: ‘as victors of my silence cannot boast‘ (Shakespeare’s silence?) or ‘my name be buried where my body is‘ (though the name ‘Shakespeare’ was plastered across the top of every other page in the 1609 sonnets and on numerous title pages too).

Consider what Stephen Greenblatt perceived through his wide and deep reading of the Shakespeare canon:

‘Again and again in his plays, an unforeseen catastrophe … suddenly turns what had seemed like happy progress, prosperity, smooth sailing into disaster, terror, and loss. The loss is obviously and immediately material, but it is also, and more crushingly, a loss of identity. To wind up on an unknown shore, without one’s friends, habitual associates, familiar network — this catastrophe is often epitomized by the deliberate alteration or disappearance of the name and, with it, the alteration or disappearance of social status.’ (4)

Consider this quote from our former Poet Laureate, Ted Hughes:

‘The way to really develop as a writer is to make yourself a political outcast, so that you have to live in secret. This is how Marlowe developed into Shakespeare.’ (5)

Consider Hamlet’s dying words to his only friend:

‘O good Horatio, what a wounded name

(Things standing thus unknown) shall live behind me!

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart,

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story.’

Consider the torn out corner where the title of this poem would have been.

The rest is silence.

(1) Many thanks to Gary Allen for bringing it to my attention.

(2) The poem uses ‘essay’ twice: once as verb and once as a noun. There is no verb form of ‘essay’ connected to writing. If we assume the poem was written in the mid 17th century, the OED offers 4a: To attempt; to try to do, effect, accomplish, or make (anything difficult) and a variation of 1a: Also to practice (an art etc.) by way of trial but this form would usually be transitive i.e. have an object – you would essay something. The verb in the poem has no object, but poets will often bend grammar to their own devices, so the practicing of an art may also be implied, perhaps as a secondary layer of meaning.

(3) Though ‘essay’ as a written composition had come into use by 1597 (Francis Bacon, following Montaigne’s 1580 Essais), the noun form of essay in this poem seems likely to accord with OED Essay (n) 1a: a trial or test, although it could be 5a: attempt. However, if it was ‘attempt’, one would need to change ‘of’ to ‘at’ to make grammatical sense (attempts at wit). Therefore ‘trials of wit’ is the best fit.

(4) Stephen Greenblatt, Will in the World (2004), p.85.

(5) Ted Hughes, Letters of Ted Hughes (2007), ed. Christopher Reid, p.120.

Peter Farey, the leading Marlovian researcher, has died aged 81. A cautious and diligent scholar, he was twice winner of the Annual Calvin & Rose G. Hoffman Prize for a distinguished article on Christopher Marlowe (2007, 2012). He was founder member of the International Marlowe Shakespeare Society (IMSS).

Peter Farey, the leading Marlovian researcher, has died aged 81. A cautious and diligent scholar, he was twice winner of the Annual Calvin & Rose G. Hoffman Prize for a distinguished article on Christopher Marlowe (2007, 2012). He was founder member of the International Marlowe Shakespeare Society (IMSS).