The Rich Writer Myth

One of the biggest myths about becoming a successful novelist is that it means you must be rolling in it. ‘Six-figure-advance’ trips off the tongue very easily, as if it were normal. ‘Royalties’ sounds juicy. Money: still something that people who want to write a novel want to write a novel for. I’m not saying it doesn’t happen. I got a very handsome £75,000 advance for my first novel, The Marlowe Papers. But that was £75,000 for four years’ work, and paid over another two years, so in essence £12,500 a year (before agent’s commission and tax). Add to that the fact that I had, like many startup businesses, launched my career through getting into debt to an amount almost equalling the advance, and you’ll realise it wasn’t actually a life-changing amount of money.

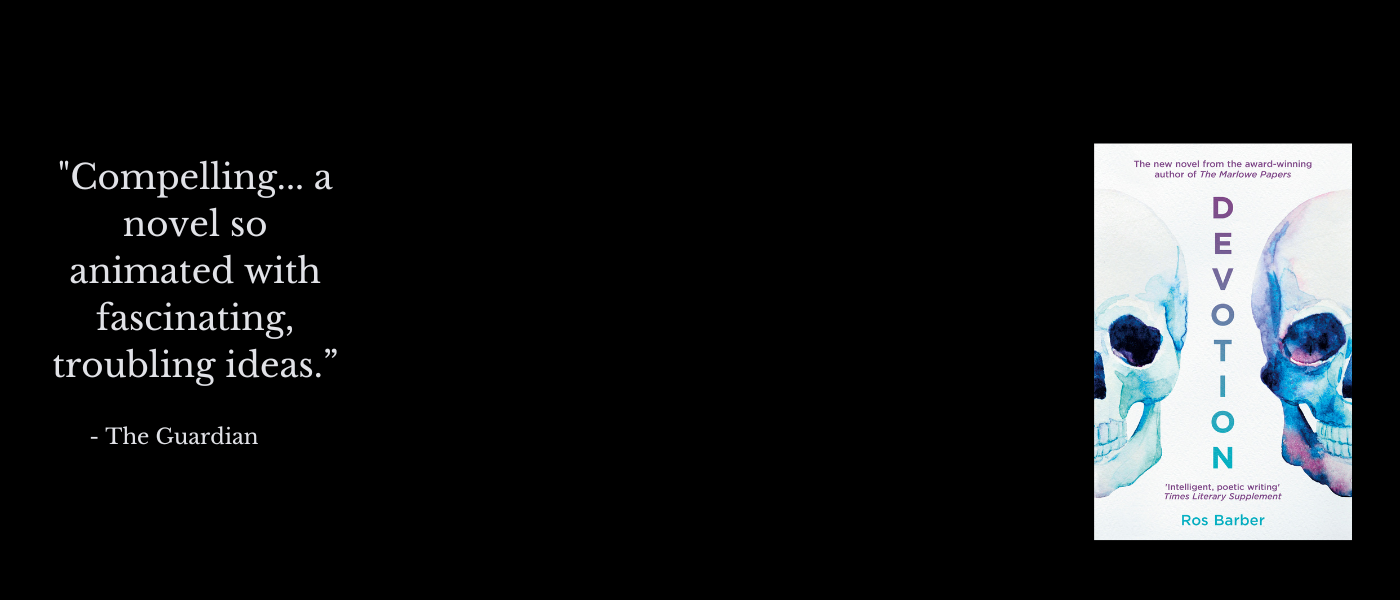

I also hadn’t realised that unless your debut novel becomes a best-seller, you’ll not get that kind of money for the second book. My advance for Devotion (2015) was £5,000. That’s £5,000 for two years’ work. This is not because it was 1/15th as good as The Marlowe Papers. Some people are liking it very much indeed. But that low advance (which is actually a pretty average advance) is causing me headaches. Thanks to the critical success of The Marlowe Papers, and nearly 20 years of teaching experience, I now have half a job (2.5 days a week) as a creative writing lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London. But that’s half a salary, which means that every month I have to find ingenious ways to drum up the other half to meet my living costs. Those ingenious ways are time-consuming, not always money-generating. In short, what they do is get in the way of writing any more books.

Writer Royalties

What about royalties? Surely if you’ve written books that win prizes and get reviewed in the mainstream press, you must be getting regular royalty cheques? Only if you’ve earned out your advance, because an advance is an advance on royalties. And the way things have gone in the publishing makes it increasingly hard for an author to earn out their advance.

Yesterday, as I was finally bracing myself to put out the begging bowl, I pulled out my publishing contracts and put my royalty figures into a spreadsheet. I found out that in order to earn back that £5,000 advance on Devotion I would have to sell 12,500 copies of the paperback through Amazon, or 7,500 copies through independent bookshops. (That’s because Amazon and other large retailers press publishers for large discounts, and the publisher passes on the effect of those discounts to the author.) If you know anything about publishing, you’ll understand that literary fiction doesn’t sell in those quantities unless the book makes a major prize list. So there’ll be no royalties on either of my novels in the foreseeable future.

Supporting Authors

The best way to support an author is to buy their book, read it, and, if you like it, tell other people about it or even buy it for them. But as far as supporting an author financially, buying their book doesn’t help them out as much as you might think. Here’s what I get if you buy a paperback of either The Marlowe Papers or Devotion (RRP £8.99). (I say, ‘what I get’, but in truth, this is the amount that will get offset against my advance, reducing the debt I owe to my publisher).

- Buy directly from the author at full price: author gets £4.50* (minus any postage)

- Buy from an independent bookshop/Hive: author gets 67p

- Buy from large-chain bookshop: author gets somewhere between 40-67p

- Buy from Amazon: author gets 40p

- But second-hand from Amazon marketplace: author gets nothing.

- Buy from second-hand bookshop or charity shop: author gets nothing.

- Borrow from library: author gets 7.67p. (And I actually receive this money. It comes through the PLR system and not via my publisher. For 2014-15 I got £69.41).

[* authors can buy their own books from their publisher at 50% discount. But some contracts will stipulate these books are ‘not for resale’ or will attempt to limit how many copies an author can sell direct to readers.]

I noted that my US sales (the US paperback is released in April) will net me even less, because they are based on “price received” rather than the recommended retail price. The US paperback retails at $15.99, but the publisher will receive something on a sliding scale between 70% ($11.19) and 30% ($4.80) of this amount from the retailer, and my paperback royalty rate of 7.5% is calculated on that figure So in the US:

- Buy from an independent bookshop at non-discounted price: author gets 84 cents (59p)

- Buy from Amazon.com (at maximum discount): author gets 36 cents (25p)

The audio book of Devotion has just been released (hurrah) but my royalty on this is also on price received, and frankly I can’t even tell what that will be, because though it retails for £16.62, I can’t imagine anyone will pay that when the most prominent price is £0.00 next to a notice that potential listeners can get it free with a trial of Audible (£0 for 30 days, then £7.99 a month). What the author will get from that is anyone’s guess.

I should add, these are not abnormal contracts. They are vetted both by my agent and by The Society of Authors. It is just where publishing is going, and is the reason why average author income continues to shrink year on year (see ‘Author’s Incomes Collapse to “Abject” Levels’).

Modern Patronage

It is clear that authors, like other creative people looking to make a living doing what they love and are good at (bringing joy to many people in the process), are going to have to look to new ways of supporting themselves. In the olden days, writers, composers and artists needed wealthy patrons. Then for a while, there was Net Book Agreement and substantial funding for the Arts, and we could mostly survive directly from the fruits of our labours. Then came funding cuts, and the internet: for love it though I do, it has ushered in Amazon and their erosion of author royalties, the free and 99p Kindle, e-book piracy, and a ‘free content’ mindset. Authors need patrons again – and hey, where are the wealthy people? Not sponsoring writers, as far as I know (though I’m prepared to be proved wrong!). The modern model of patronage, Patreon, is based on crowdfunding. You can become a patron of the arts for as little as $1 /84p a month. That’s $1/84p you probably won’t notice, but if enough people do the same, your chosen artist/author really will. Check it out. The continued survival of literature written by anyone other than the wealthy and privileged could depend upon it.

If you like anything I’ve written; if you’d like me to write more; if you’d happily buy me a cup of tea if you met me, then maybe you’ll consider becoming my patron. You can do this for only $1 (84p including VAT) per month. Patrons will get regular ‘insider’ updates and at certain levels get other rewards too (first edition signed and specially inscribed copy, name in acknowledgements etc). Find out more by clicking here.

Ros, this is an absolutely fantastic piece. Well said and needed to be said. The myth of rich authors needs to be exploded – and hopefully changed! Well done for adding to the debate and enlightening a few people in the process.

A beautifully clear and concise description of the problem, and in part why I have chosen to stick to non-fiction and occasional ghosting for others. It’s worrying how many people – even keen readers – think it is OK to ‘steal’ e-books, excusing this on the grounds that they may later buy another one. And worrying that bookshops and even festivals expect authors to speak for nothing while knowing that only a tiny fraction of attendees will buy anything at all.

I understand why Alexander McCall Smith writes 200 books a year now. How much might an author make if a film company or TV want to option?

I don’t have personal experience of having a book optioned for film or TV. From this blog post – http://www.scriptmag.com/features/story-talk-should-i-take-a-1-option-on-a-screenplay – it seems $1 options are frequently offered, but that writers should ask/hope for between $1000 and $5000 (or in the UK, between £1000 and £5000, since our prices usually seem to match, even though our exchange rates are not 1:1). I just signed the option for an opera of The Marlowe Papers which had a headline figure of £1000: that’ll be around £800 after two sets of agents have taken their cut (plus VAT). Writers get more if options are actually picked up and the end-product (film, TV series, opera) is developed, but that doesn’t necessarily happen.

I don’t think this can be right. Where did you get this number? It seems a bit extraordinary, since it implies a book in slightly less than two days every day of th year (including weekends and Bank Holidays)

You have a point, Billie! I hadn’t even noticed Sandra’s ‘200 books a year’. I suppose that could conceivably be 20, although even that seems a bit ludicrous – but then I vaguely remember years ago hearing (was it true?) that Barbara Cartland dictated a book a fortnight, which would indeed be 20 books a year with a couple of weeks off for Christmas and Summer hols. But 200 must surely be wrong.

We live in a new age. The myth of the Rich Traditionally Published author is over, but there is still plenty of money to go around for those who are willing to work at being both publisher and author.

I have only eleven novels, seven under Brian D. Meeks and four under Arthur Byrne, but that is still enough to earn five figures a month from Kindle sales. Of course, ebook sales aren’t the only revenue stream, there’s translations, audio, and print.

It takes a lot of work and I spend less than 10% of my time writing, a notion that may not appeal to many writers, but if one wants to earn a reasonable living as a writer than I feel it’s worth it to learn the business.

And the financial rewards aren’t the only benefit…

– Complete control of the product from choosing editors (I have two with 10 and 25 years experience who are brilliant) to cover artists and we never give away our rights.

– Speed to market. Traditional publishers aren’t even in the game in that regard. If I finish a novel today, it’ll be through editing and beta readers within a month and then it’s time to launch

– 70% of Kindle gross sales NOT a fraction of Net-Profit (which means that those lovely NY Offices and the accompanying rent, it’s coming out of your book, too, along with every marketing penny they spend, all before the author share is calculated) Okay, that’s a financial reward.

– Pricing control which leads to marketing control.

– Making decisions about boxed sets. I have two, one for my mystery series and one for my science fiction series. They provide fantastic revenue streams. And what about Audio and Foreign rights? Those are all under the control of the self-published author.

– Accurate sales and marketing data. This is no small thing and being able to analyze results gives one much greater control. (Note: I’m a former data analyst and I love math, so this may only be a benefit to me because I’m nerdy.)

The point is that though it’s time consuming and there are a lot of tasks one has to do that have nothing to do with writing, there is also the satisfaction of creating the book from start to finish beyond just the word smithing.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting a Traditional Deal if one isn’t trying to have a lifelong career as an author, but for serious writers, becoming publisher and author is (in my experience and that of my author friends who all make WAY more than I do) the only way to go.

Still, it was a really good article and does shed some valuable light on the challenges associated with the traditional route.

My thoughts entirely. No upfront advance to earn out but 70% royalty payable instead. Indie publishing is the smarter economic model.

Totally agree – the ONLY way to go in this market is to self-publish and self-market” “The Watch: Churchill’s Secret War.”

Agreed. This article sheds light on one area, but for the adventurous authorpreneur the glass is half full. Be willing to work hard and stay the course, whatever you decide your course should be as an authorpreneur.

I’ve read this comment a few times, Kori, and I’m not entirely sure what it means. I think that’s because that second sentence is an abstraction/generalisation. I’m an adventurous ‘authorpreneur’ who works her tits off, but I’d rather be an adventurous author. I’ve had to learn the business side but it is not really the best use of my talents. As an optimist my glass is always fully full, but when my income glass is half full (month after month) despite working 60-70 hour weeks, the going can still get pretty gutty. Thanks for your comment.

Thanks for this honest assessment, Ros. I was telling a book group I spoke at the other week – when they asked me how much I get per book – that I would only earn 40p on anything they bought on Amazon. And that was only after I’d earned back my advance. Which might be never. They nearly fell off their collective sofa.

I too lecture in creative writing part-time at a university to make ends meet. Or at least attempt to. I would, however, like to point out to the self-publishers above who have lectured you that working hard and being an ‘authorpreneur’ is the ‘only’ way to make money that that simply is not true. I have self-published and am now traditionally published. I do not earn much as a traditionally published author but I earn more than I did as a self-publisher. (And I write genre fiction).

I published 7 books in 4 years and in that time only one of them went into profit – and that less than £100. And before anyone says it’s because I didn’t work hard enough, my friends and family who barely saw me for 4 years will tell you that I worked my butt off. So hard in fact that I attracted the attention of two separate traditional publishers who took me on (one for my adult books, one for my children’s books). Although I did not go into self-publishing in order to attract a publisher, I am so glad that I did. I simply could not keep going the way I was – financially, physically or emotionally.

I could no longer take the feeling of inadequacy every time I read an article by a self-publishing success story telling me if only I worked harder and smarter, did all the right social media promotions, spent 90% of my time marketing and only 10% writing – oh and subscribed to their blog or downloaded their latest how-to manual – I too could earn at least 5 figures a month. But the reality is, of dozens of self-publishers I knew, I was probably the most successful. I’ve come to realise that only a few traditionally published authors will earn a decent living from writing alone – and the same is true of self-publishers. Yes I earned more per book as a self-publisher – a lot more – but my distribution was pretty much limited to Amazon and a few indie bookshops. My mainstream publisher has access to markets I was never able to reach. I have just sold Korean translation rights on my children’s books. My adult books have just been published in America – and not just ‘made available’ through listings on Amazon or Barnes and Noble. I’m not – and probably never will be – in a position to earn my living solely from my books, but I will no longer believe the myth that that’s because I don’t self-publish.

So well done Ros for making any kind of living from your writing – that’s more than most people do. And if you add in your job teaching writing, that you would not have got if you weren’t such a good writer yourself, you are blessed indeed. It beats packing shelves in a supermarket any day.

Thanks Fiona. I couldn’t agree more! I love my life, and I count my blessings every day. I also love my job teaching writing, not only because it’s a joy to impart useful information (and watch your students blossom) but because I’m fortunate enough to work in a great department with colleagues I love and respect and terrific, engaged students.

I thank you for correcting some of the impressions being given in these comments that self-publishing is the answer! As you point out, it is damn hard work, especially if you don’t want to spend 90% of your time marketing … and doesn’t necessarily lead to a good income either, no matter how good your books, or how hard you work. I think I’ll be doing a blog post on this shortly!

I love being traditionally published, and both my publishers are terrific, and have worked hard to get my books out into the world. It’s just not so easy these days for any of us (authors and publishers alike) to make sufficient money from our hard work! As you say, trad publishing opens up things like translation markets, and we never know when something like that will really catch fire. All the best to you, Fiona: may we both be on the other side of financially comfortable before too long!

I don’t want to give the impression though that I think self-publishing is never as good as traditional publishing – in terms of quality of product. That is not always the case. There are some fantastic self-published books out there that may never get noticed by trad publishers. There are also some awful ones (for many of the reasons you’ve given above). However, I know and highly respect a number of self-publishers who do a great job with both the writing and marketing aspects of the business. My gripe is with the dream industry that has built up around self-publishing. I am very happy with my traditional publishing deals but that does not mean I will never self-publish something again in the future. But if I do it will be with no expectation of ‘making it big’.

Thanks for your comment, Brian. In my view, for all its problems, traditional publishing is the *only* way to go for someone who writes literary fiction. I am grateful to my publishers, and am conscious that they have done the very best they can do to get my work ‘out there’. With genre fiction like yours, self-publishing can work a treat (IF you can build a platform, IF you don’t mind marketing and are good at it); those who read genre fiction don’t care whether its self-published or not, they just want an accessible yarn, and an author of genre fiction is not dependent on critical acclaim and literary prizes to build their reputation and following.

Literary fiction, in comparison, sells in small quantities, and will struggle to reach its readers at all (few as they are) unless it comes to the notice of the mainstream press and the panels of literary prizes. Literary fiction authors become bestsellers (and make real money) if they can win the Bailey’s or the Costa, or make the Man Booker shortlist, but it is, as Julian Barnes said “posh bingo”. Self-published books are not eligible for most literary prizes. Nor, on the whole, do they get reviewed in the mainstream press, or get their authors appearing at major literary festivals. All of these things are essential to authors of literary fiction.

Readers of literary fiction also care about things like cover design and tight editing; things that self-published authors tend to skimp on, from my experience. If you are not a professional artist/illustrator/graphic designer (or you do not know one), you cannot knock up a great cover on photoshop or get someone to do it on fiverr.com; it will always look amateurish. These things cost money, and self-published authors tend to keep their production costs low (with good reason). With genre fiction that doesn’t matter much; with literary fiction it matters a great deal. So no matter how lucrative self-publishing might appear to be (and plenty of people find that 70% of nothing is nothing), it is not a path it is worth my while (as an author of literary fiction) to tread.

… And yet there exists phenomenal snobbery in the literary world towards those who have another (non literary) job. This desperately needs to change…

Interesting article. I must admit I have bought books in pretty much all the ways mentioned. Direct from the author, new from bookshops (independents and chains), new and second hand from Amazon, and from second hand shops and charity shops. I’ve never pirated an E-book although I have downloaded a number of books for free where (as far as I am aware) the copyright has lapsed (Arthur Conan Doyle, Bram Stoker etc) and taken advantage of promotions (I downloaded a novel for free out of a choice of 6 recently which I would probably not have bought otherwise but might yet read).

I haven’t yet looked into Patreon, although now I’m reminded of it, I remember reading an article about why Amanda Palmer was using it. I still feel bad for merely promoting one friend’s kickstarter and forgetting to go back and actually contribute myself, but did chip in to another recent crowdfunding request (a musician).

One thing I enjoy about the internet is that it makes it terribly easy to look someone up and drop them a note saying “I enjoyed your [book/CD/program/talk]” and I always feel happy when someone is kind enough to reply. I appreciate that not everyone can but often remember and feel more engaged with those who do.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m a massive fan of the internet. And one of the best things about it, as an author (apart from the ease with which can research any topic) is the connection it provides to readers. Twitter is my favourite social media platform for this reason. I was struggling to see the point of it until my first book was published, but the instantaneous reactions from readers (and the ability to respond to them) made me understand its value to authors. This is how authors can build a community, albeit a slow, one-by-one process. Thanks for your comment, Nick. (And I have bought books in all these ways too).

Hi Ros,

This article reached the very soul of my being. I gave up everything to write, and your words resonate very loudly as I approach the breadline, not the deadline. I feel suffocated under the Amazon blanket of hopefuls. I can never tell if my work is good because no one can see it to buy it, and give me feedback.

I have an author platform at Jamesmediacompany.co.uk or http://www.jfstevenson.co.uk where I’m building my profile and that of my poetry club. It’s a work in progress, however I would like very much to republish your article, and perhaps draw some patrons to the cause?

Please let me know if that’s ok?

Hi James. Always glad to touch another’s soul, of course. But no, you can’t take my work. The only benefit to an author in providing free content on their website is in the hope that it might bring people to their website. Not other people’s! You are asking to take a copy of my most popular blog post ever (the sweat of my brow; hours of my time) – 5000 views in its first 24 hours – and reproduce it on your website, where it can compete with this one for Google rankings when authors search about money. What’s more, as I understand it, Google’s algorithms penalise duplicate content so you would not only be doing yourself a disservice, but me, too!

There is no quick solution to your dilemma. I have had a website, and been blogging, for over ten years, and been writing poems, short stories, novels and articles since I was 9 years old (and very concertedly for the last twenty years), in order to get to the point where I have a sudden influx of a few thousand visitors to my website. You will need to do the same. By all means write your own article about being an author on the breadline, and by all means link to mine as its source of inspiration – as the thing to which you are responding – but do generate your own original content. If an aspiring author cannot do that, they are sunk.

Incidentally, just linking to your website from the comments section of a high-traffic article like this one will have helped you. Let that, and the advice I have dispensed to you, be enough! Blessings and good wishes to you, and may you get where you intend.

Hi Ros,

An excellent article and a brave one too, as not many authors (or Brits for that matter) like talking about earnings. If it’s possible to get over the ‘legitimising’ effect that being published gives you, as well as the speaking engagements and the invites to literary festivals, self publishing can be a more financially lucrative route. Sure, you have to do all the things a publisher does, but all of those are available from people, most likely made redundant by many of the big publishers. I long suspected that what you wrote is true, now I know. Thanks.

I don’t feel a literary fiction author can succeed without the ‘legitimising’ effect of trad publishing. Success for authors of literary fiction is literally *all* about mainstream press reviews, prizes, and literary festivals, and none of those are available to someone who self-publishes (let alone high quality cover design, great editing input, marketers and publicists, a marketing/publicity budget etc etc). Despite what I might appear to be saying, I don’t do it for the money. I do it for love, and the hope of writing something of lasting value; something that might still be read when I am long dead. Even though I would like it to pay me better, so that I could do more of it – and because that would signify that I and my writing are valued – money isn’t everything.

Hi Ros

I wonder if Amazon could be persuaded to set up a sort of Author’s tip box, so that when they remind you to post a review they could also give you the opportunity to tip the author £1 or 50p. If I enjoyed the book and could pay by 1 click I’m sure I’d do it.

A fine idea. Though I can’t imagine how they could be persuaded, unless they were allowed to keep a decent percentage of it. 😉 And who would persuade such a behemoth?

I guess it would have to be someone like the Society of Authors and their US equivalent. But it might appeal to Amazon to be able to present (market) themselves as the saviour of struggling artists.

YES to all.

PLUS : the internet modifies reading behaviour — the internet modifies our readership.

As authors, we must adjust to in the digital age and how the internet modifies the experience of reading, and consequently also the expectations of readers.

A book is a long thing; a unique thing, a one-way communication. Reading on the internet is two-way. I can leave responses and comments wherever I want. I can have twenty, thirty windows open simultaneously and stop and start reading anything. I can navigate to suit personal curiosity and attention span. In short, I can create my own reading material. From a million little pieces on the internet. It happens to me a lot, too. Especially when I go on Wikipedia.

It’s different from reading a long, one-way communication from top to bottom. When I grew up, the internet was nowhere. Until my late teens, I only read printed matter. Thinking back, it was divine; the internet changed everything.

How much old-school readers, who prefer books to sites, will still exist three too four decades from now?

I don’t mean to judge the intellectual implications of this burgeoning change in society’s reading practices. Some believe it to be culturally toxic, but really, the jury’s still out on that one. On the other hand I am pretty sure we won’t be selling any more “long things” to the people of the future, and this is why our money will stop if we continue to produce books like in the old days. Like Kodak, we will go out of business.

Personally I have always been fond of developing “choose your own adventure” conceptual novels, and experimenting with programming. I did attempt it once. But it sounds dorky, and mildly upsets my aesthetics of literary writing.

Reading a book and browsing websites are not the same thing at all. One is immersive in a way the other is not. One is intellectually stimulating whereas the other is shallow. It is like comparing a four course meal at a Michelin starred restaurant with a drive-through McDonalds.

People have been predicted the demise of the printed word for years. Waterstones came to the brink of collapse but now they will tell you business is flourishing. The internet cannot replace the printed word. I have 5 girls all under the age of 13 who are voracious readers who bear testament to that. I cannot provide them with reading matter quickly enough, and they all prefer a proper book to an e-reader.

Anyone who finds their interest in novels supplanted by reading snippets from the Internet was never a lover of literature in the first place.

I gave a lecture about publishing to a High School Class and pointed out that the average author would make more money as a NYC sanitation worker than as an author. After 5½ years, the salary jumps to an average of $88,616 dollars – I would like to make that a year off my writing…

Great article! Especially the part where you break down how much an author gets paid depending on seller. I would love to spread the word on this, as I know many people would favor the most author-friendly option when choosing where to buy their books, even if that option is a bit more expensive. So…question: do you happen to know how much authors tend to get through iBooks vs Kindle (vs other e-book sellers)? (I go with iBooks based on the assumption that they’re more fair simply because they’re not Amazon, but I realize this might be a faulty assumption.)

Bigger question-Do you know of other sources that could help readers make more informed decisions when buying books? I would love to help spread the word. So far, your article is the only one I’ve found that offers concrete stats, and I’ll be sharing it. Thanks!

Thanks for you comment. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

My contract says I get 25% (so a much higher) royalty on e-books (no distinction made between Kindle and iBook) on “price received”. The question is, what is the discount given to the e-book sellers which will determine price-received? Do Amazon demand a higher discount than iBook? At the moment I do not know.

As to your other question, no, I know of no other sources of information which would help readers make informed decisions when buying books. Which is partly why I wrote this one.

Ros, this is an honest piece. 10 years and seven books later, I’m still explaining to people why I’m not a jetsetting, champagne-guzzling, million-dollar author. But, still, I write. Because, that’s what writers do. Thank God for the other job; the real one that keeps a roof over my head and allows me to keep on writing.

Thanks Abidemi. Yes indeed!

Thanks. I knew book writing wasn’t a get rich quick scheme, but the hard realities are still shocking.

Your article might just have given me the strength to face up to a few more years / decades of corporate drudgery.

Hi Jonny,

Well, if you can find some kind of middle-way (something that involves writing, perhaps, or at least more enjoyable than corporate drudgery), I’d see if you can’t start heading in that direction.

Ros

The secret to making a living writing is not in whether you self-publish or don’t, it’s in writing something that a bunch of people want to read. If you do that, you are better to self-publish and keep more of your money. If, however, you are writing something not that popular, you’re probably better to go with a traditional press if they will have you.

One wonders, however, since you are in the position of supplementing your income anyway, if writing cozy mysteries or space opera or something else for the hoi polloi under a pen name and self-publishing it might not be an enjoyable way to finance a literary fiction career.

All the best!

But there are so many downsides to self-publishing fiction, many of which I list in my follow up post on The Guardian blog. Some apply only to literary fiction, but the marketing one (and the expert team one) apply to popular fiction too. I have no interest in spending 90% of my time marketing the popular book you suggest, and I would have to, to get any kind of readership/sales. Under a pen name, I couldn’t even rely on a small market of people who already like what I write – I’d be starting from scratch.

And that’s even assuming I could write popular fiction successfully. I happen to know that I can’t. My first husband, who had no respect for the kind of thing I *was* writing, insisted I try writing something “that would sell”. At the time I was bending myself out of shape to try to win his love/approval, so I listened to him. I got 50,000 words through that pile of horse crap. Unable to go on without some hope that it would actually be worthwhile on *some* level, I sent the opening chapters and a synopsis to several agents (1990s, pre self-publishing), and every single one of them said the same thing. To paraphrase: “we can tell your heart’s not in it”. We write the kind of books we love to read. So I am doomed to write literary fiction, whether it sells or not.

I sense that we’re in an ‘in between’ state, and in a few years time the economics of authorship will make a bit more sense. Having said that, the number of people with the means to complete a novel is vastly greater than 50 years ago, so it will remain a steep pyramid, with some earning great dosh, and most earning little.

I have to take issue with the folks who say that self-publishing is the only route. I’m not familiar with their books, so won’t comment on their quality, specifically – though I’ve read a few self-published books and understand why they couldn’t find a conventional publisher!

Most self-published authors earn vastly less than the pitiful sums available to conventionally-published authors – usually a sum approximating to zero. The notion that an author *should* spend 90% of their time on marketing is, simply, daft. Next time I need an operation I’ll criticise the surgeon if s/he has been wasting their time doing surgery or attending training courses.

On reading all the above I have been persuaded give up my dream of becoming a published writer, I shall dump my manuscripts in the bin, chuck away my pen for good and be grateful for my job at the local supermarket.

I am currently able to pay my bills and intend to keep it that way. Next time I read a book I now know that I shall be doing so from a privileged position – not as an author, teacher, or university lecturer, nor a conjurer of magic characters, places and themes that carry readers into other worlds – but as a 36 hours a week supermarket cashier on minimum wage who has no worries and no pointless dreams.

Thank you for the shot of realism.

Kate

Kate, I sat on your comment for a few days wondering whether to approve it or not, because this is my home and I don’t necessarily want to fill it with deep sarcasm. You are Kate North, writer and lecturer at Cardiff Metropolitan University, are you not? So you are already living (at least a version) of your dream and you are already a published writer. You are in fact some way further on than I was when I had two poetry collections under my belt (as you do), because I didn’t have a lectureship then.

Your comment suggests that you think I wrote this article in order to discourage those on the writing path. I would never do such an thing, and indeed have spent the last 20 years (when I began teaching creative writing) encouraging other writers and helping them to achieve their dreams. Although I myself have done plenty of minimum wage jobs (including shop work, bar work, cleaning and waitressing) and sometimes in the early stages these can be necessary just to put food in one’s mouth, not for a moment did I ever think of myself as anything other than a writer. I encourage that in all my students too… and indeed anyone who reads this article and wonders whether the struggle to be recognised as a writer is worth it. It always is. And for all the vagaries of the freelance writer’s life (now supplemented by a part-time lectureship) I make much more money as a direct and indirect consequence of my writing than I could ever do in on minimum wage.

I imagine this comment is more to do with Guardian piece than this blog post. If so, please read my follow up post for a little context. Thank you.

On my own account, I used writing groups, beta readers and editors in an effort to make up for my non-literary background. There’s only so far you can go without it taking over your life. The gentleman who reports the benefits of complete control is the exception. With my business hat on — in another life I’m an accountant — I’m comfortable in the notion that, in the main, writing doesn’t pay; a few winners and lots of also-rans. Although that’s how it is, it’s incumbent on us to ensure our product is as good as we can make it.

Keeping my business hat on — from a that perspective, traditional publishers need to get their houses in order. I say more on that here: https://discussion.theguardian.com/comment-permalink/71357886 The debate about traditional and self-publishing will go on.

I use POD to experiment— mostly in genre areas that don’t seem to get much attention. There’s a lot to write if you stay clear of fads. This isn’t commercially attractive. What would I do? The options are write what interests me, or pump out something I don’t believe in, in the hope that a me-too offering is a stepping stone to (eventually) a contract that I’ll hate. I’ve talked to writers on that treadmill.

On a more direct line, I have been writing since 2009 and have just put out my first ‘normal’ novel. I want to know if it works but the logic of Amazon means it has to be ‘finished’. Do we draw a line in time and say “then is when I stopped growing as an author”? Not everything is complete.

Hi Ros,

I have been writing for 25 years (I just turned 70 last week) and can honestly say that in all that time what I have made in monetary terms wouldn’t keep me in Metformin tablets. Very few writers make money. Samuel Johnson once said that ‘only a blockhead writes for anything but money’… well I hate to tell you, Samuel, but there are an awful lot of blockheads around these days!

I mostly write plays, 20+ to date, but I have also self published a number of books, both fiction and non-fiction, and all of them only make a pittance when I get my monthly Amazon statement.

I am clearly not in it for the money, though perhaps I was mildly seduced when my first published book had a film option taken out on it – it paid £1000, though I only received half that, the publisher getting the other half – and I probably thought ‘this writing game is easy’! A similar thing happened with my first play -Money From America – which had a sold out run and broke the box office records at a London fringe theatre. Unfortunately, it has been all downhill since then!

For most writers I think it like a drug; they write because they have to have that daily fix. I suppose if you can make a living out of it as well then it becomes doubly pleasurable. I am still writing, still getting my plays on at London fringe theatres, still getting great satisfaction from it, so despite the ‘penury’ I will carry on.

Thank you for highlighting state of affairs most writers have to put up with.

Tom O’Brien

Very interesting article. I work for successful, traditionally published authors of genre fiction, so I’m sort of on the fringes of being in the publishing industry. While I believe that excellent books can come through the self-published route, it’s undeniably true that a lot of terrible books are coming that way, too. With the advent of ebooks, once a book is published, it almost never goes away. Every author is now competing for the readers’ attention with an ever-growing number of books.

Your point in the Guardian article about the loss of the gatekeeper is a good one. I could write a story this week and have it uploaded as an ebook next week. No editing, no revisions, no concern for the readers’ pleasure. It would be terrible, but it would be there, clogging up the search results. (That said, I know a lot of self-published authors who send their books through a rigorous editing process on their own dime, and who care a great deal for the quality of the product they’re putting out there.) For this reason, when readers discover an author they love, they MUST sign up for that author’s mailing list to ensure they don’t miss the next book. Otherwise, their chances of stumbling across it are minimal, and the author’s chances of sustaining a career are lessened.

It amazes me that people who truly love to read clamor for free books, some even stealing them through pirating. They don’t seem to make the connection that the authors they love need to make a living at it in order to continue writing. If we want good books, WE NEED TO BUY BOOKS.

All the best to you.

Very interesting article! Thank you. I wondered: Book prices generally drop in the first few months after they’re released. Does the lower price affect the author’s profit as well as the retailer’s? I normally wait for those couple of euros to be knocked off, but maybe I shouldn’t! 🙂

Yes, generally speaking, the higher the discount, the less the author’s royalty.

I was fascinated by the figures in this article. I am glad I don’t have to make money from writing. I have self published a book, but now I have done that it’s up to people to read it if they want. I am not inclined to bash my pan in trying to sell anything. I suspect the real money lies in the ebooks that hook people into further products, courses, cds etc.

I do find it sad that writers of literary fiction can’t just focus on their writing, but must spend the bulk of their time doing other things. At the end of the day the point of writing is self expression if anything comes of it that’s great.

As you say you write because you love to write, I suspect regardless of income you could no more stop writing than breathing. You don’t write to make a living, but because writing is your life. I hope you have a financial breakthrough soon, preferably starring George Clooney!

Oh wouldn’t that be nice! Thanks, Rory.

Just saw your article in the Guardian. Very interesting. The question I have for you – why do you write? Clearly it’s not for the money, so why? What’s in it for you?

Writing (well) is an artform – and like any artform, the artist does it because they feel compelled to do it, feel most alive when they do it, and could do nothing else. Since I was very young I had a passion for writing and was convinced that I was a writer. I was first rewarded for my writing at the age of six and had plenty of other people who praised my writing and thus encouraged me to do more of it. Though I didn’t actually *need* that encouragement – I wrote anyway, it was part of my identity. At the age of nine I typed up a bunch of stories I had written on my mum’s typewriter and sent them to a publisher. It is a vocation, a passion, and has always been (for as long as I can remember) ‘who I am’. And for all that literary fiction doesn’t necessarily bring in a lot of cash in terms of royalties and advances (though the advance for my first novel was *amazing*), it has been my sole livelihood for 16 years now, not only through a salary which rewards me for my writing expertise (my university post) but through grants, prize-money, reading fees, commissions etc. So no, I don’t do it *for* the money, I have learnt to do it well enough that ‘being a writer’ sustains me. Which is, no question, every artist’s dream.

This is the second time I have heard Patreon mentioned recently. The concept is an interesting one. Though I suspect that most patrons will need more than the work in return. Egos must be massaged and I am not sure how this could be done. More clever marketing needs to be done to reintroduce the whole concept of being a patron, modernise it and raise the profile.

How often is a patron also a partner?

The balance of household jobs, childcare and the bank account exist on one hand with more intimate familial and personal satisfaction on the other.

‘Do not expect the house to be tidier when all the children are at school.’ There was a raised eyebrow, but no surprise. ‘I will be writing more, not tidying more.’

Yes, that is what has happened and will continue – from unpaid domestic work to insignificantly paid literary endeavour. All my better remunerated qualifications and skills be damned.

I would never call a partner a patron although of course some partners do indeed financially enable a writer to write. A patron support a writer without there being any other kind of relationship in place. So by that definition a partner, even though supportive, would never be classed as a patron. In my case, my partner practically enables my writing by doing all the childcare household chores that would prevent me from giving my time to it, but I am the only one in a position to drum up any kind of income… so in the absence of sufficient support from Patreon (multiple crowdfunded patrons) I must work full-time.